The war I never went to

I had begun parachuting (skydiving) in November 1969 although it was strictly sport jumping, even though I was then in the Royal Air Force (RAF). I did make 2 military jumps for aircrew training, but that was all.

After I left the RAF in late 1973, I trained as a sport parachute instructor, and worked professionally for 4 years at two leading parachute centres in Britain. It was a wonderful time, training a long string of novices, and then persuading them to step out of a plane at considerable height!

Plus I made demonstration jumps at public events – great for the ego, if sometimes a little tough on the nerves….

By 1977 I was ready for a change (to cut a long story short), and I interviewed for a job at a major parachute manufacturer north of London. It was a junior position to begin with, but I oversaw various small design projects, and helped with different aspects of parachute development. Then one amazing day, I was officially adopted as the company test jumper, and began to make live jumps on our prototype parachutes.

The design that emerged was a canopy of about 32 square metres, much larger than today’s parachutes, but large enough to support a fully equipped airborne soldier. The company designation was rather mundane: ‘PB11’, but it was also named ‘Skyknight’, and that sounded far more glamourous. I made the first live jump on the prototype chute in January 1980, and went on to use it for regular ‘fun jumping’ and demos, as well as taking it overseas (Pakistan, Italy and Denmark) to demonstrate to other potential military customers.

The design that emerged was a canopy of about 32 square metres, much larger than today’s parachutes, but large enough to support a fully equipped airborne soldier. The company designation was rather mundane: ‘PB11’, but it was also named ‘Skyknight’, and that sounded far more glamourous. I made the first live jump on the prototype chute in January 1980, and went on to use it for regular ‘fun jumping’ and demos, as well as taking it overseas (Pakistan, Italy and Denmark) to demonstrate to other potential military customers.We produced another 22 assemblies for pre-production assessment by our ‘clients’, and in a parallel development we even built a radio-controlled version, which eventually hit the ground at considerable speed, and ended THAT programme forever!

In the excitement of running development programmes, it’s easy to forget the end use of the equipment being worked on. Even easier, in peacetime, to ignore the military role that our equipment could play in conflict. And we never dreamed…

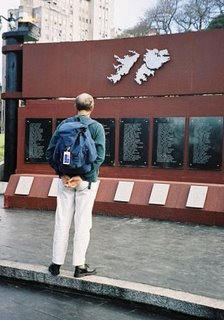

In a few weeks in 1982, things changed. In the middle of Anglo-Argentine talks to try to resolve issues of sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Las Islas Malvinas), Argentinian Special Force troops came ashore near Stanley in the early hours of Friday 2nd April, and in the course of the day succeeded in overwhelming the British garrison, and capturing the Governor-General, Rex Hunt.

Reinforcements rapidly arrived from the mainland, and the islands were secured in Argentine hands. The scene was set for the 10-week Falklands Conflict.

The Easter holiday was the following weekend, and in England most of us went about our normal business. During the long weekend I met my future wife for our second date, and we went paragliding. Easter Monday was a holiday too, of course, so it was back to work on the Tuesday the 13th.

I arrived at work at 8 o’clock on Tuesday morning, as usual, and was met at the door by my boss, CJ. Something was clearly up, and he rushed me across the road to the No 1 factory to meet a man (called Chris, I think) who was driving a very plain yet obviously military Land Rover.

Production and Inspection would examine each of the sub-assemblies straight away, and any repairs or modifications (to bring each assembly to the current standard) would be done immediately. Then the Chief Packer and his merry man would re-assemble and repack each reserve parachute, whilst I would pack the main parachutes. This was far from standard procedure, but in the circumstances, nobody thought anything of it.

CJ organized a packing area, by taking over the games room next to the staff dining room. We cleared away the table tennis table, and that gave enough floor space to lay out and pack the Skyknight main parachutes. We hadn’t then mastered packing a ram-air parachute on a bench – it was normally done on the ground anyway - so it was easier to go with what we were familiar with.

Inspection kindly gave me an assistant. Our chief inspector (who was a casual jumper himself) found one of the girls in inspection, Hazel, who had also done a parachute course, and he arranged that she and I would pack the chutes up to the point of attaching them to the harnesses.

It was a huge task really, but we got stuck into it, and systematically worked our way through the growing pile of inspected main canopies. Time went by very fast, and we worked very well together, Hazel and I.

I don’t recall when we finished, but I seem to think we worked into lunchtime, as a number of workers were a bit put out, initially, that they couldn’t get in to play snooker or table tennis.

Somewhere in the midst of all the packing a thought struck me, and i asked out loud *What are the Argentine national colours?*. Everyone standing about began to laugh - in the terrible irony of the moment, we were surrounded by bundles of pale blue and white cloth

Eventually it was done. The packed main parachutes were attached to their harnesses and closed into their packs by the Chief packer, and Chris loaded up his Land Rover and was off. I had no idea what the plan was, but it was obvious that the SAS was getting serious, and the Skyknight was likely to be used in anger.

On Wednesday we did the whole thing again!!! The other 11 parachute assemblies had been found, and once more driven overland in the early hours. We discovered during the day that the first batch of parachutes had been taken directly to waiting troops, and they had made a night jump into Wales (into a region resembling the terrain of the Falklands) by way of a training exercise. Clearly the SAS were getting serious.

Nothing more was heard of our equipment. The SAS are very secretive, and would even decline to mention parachute problems when it might ‘give the game away’.

But weeks after the end of hostilities I had cause to visit one of the military trials units, where our parachutes were evaluated by the Air Force. During conversation one of the technicians referred to a plant pot full of moss from Pebble Island, which stood in his office.

But weeks after the end of hostilities I had cause to visit one of the military trials units, where our parachutes were evaluated by the Air Force. During conversation one of the technicians referred to a plant pot full of moss from Pebble Island, which stood in his office. ‘How did you get moss from Pebble Island?’ I asked him

‘It came back in one of your Skyknights’, was the reply.

They must have picked it up when they collected all the equipment after the war was over.

Labels: Kiwi_John, Life Story

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home